Current Projects

Invading Medicine: Physics in the formation of Radiology

(Book manuscript in progress)

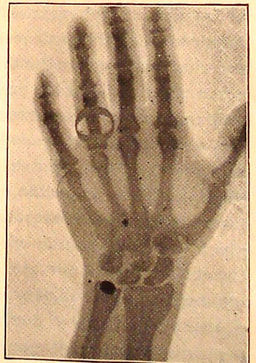

At the heart of this book are questions about the dynamics of interdisciplinary collaboration in science and medicine. In January of 1896, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen circulated startling x-ray images of his wife's hand, sparking a frenzy of excitement over the possibilities of this new technology. The equipment needed to produce an x-ray image was available in most physics labs, and within weeks, physicists were complaining about the distraction caused by doctors bringing in patients to diagnose fractures or locate stray bullets. Once doctors were able purchase their own x-ray equipment they no longer had to rely on the patience and goodwill of their neighbourhood physicist. But even as this technology moved out of physics labs and into medical spaces, physicists and physicians continued meeting to share research, to work together to set safety standards and to evaluate methods for measuring a dose of x-rays. This book tells the untold story of this collaboration in the first decades of the twentieth century, asking how these individuals worked together, often with very different goals, tools and training, to make sense of the properties of these new rays and to develop a set of best practices for their use in medicine. Rather than being a story of compromise and mutual transformation, I argue that the values of the physicists increasingly shaped the emerging field of radiology.

(Book manuscript in progress)

At the heart of this book are questions about the dynamics of interdisciplinary collaboration in science and medicine. In January of 1896, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen circulated startling x-ray images of his wife's hand, sparking a frenzy of excitement over the possibilities of this new technology. The equipment needed to produce an x-ray image was available in most physics labs, and within weeks, physicists were complaining about the distraction caused by doctors bringing in patients to diagnose fractures or locate stray bullets. Once doctors were able purchase their own x-ray equipment they no longer had to rely on the patience and goodwill of their neighbourhood physicist. But even as this technology moved out of physics labs and into medical spaces, physicists and physicians continued meeting to share research, to work together to set safety standards and to evaluate methods for measuring a dose of x-rays. This book tells the untold story of this collaboration in the first decades of the twentieth century, asking how these individuals worked together, often with very different goals, tools and training, to make sense of the properties of these new rays and to develop a set of best practices for their use in medicine. Rather than being a story of compromise and mutual transformation, I argue that the values of the physicists increasingly shaped the emerging field of radiology.

Mechanical Womb and Artificial Mother: Designing the Infant Incubator 1900 - 1940

In this new project, I investigate the design of early infant incubators, devices which seemed able to replace or even improve upon mothers' bodies and care in particular ways. Invented in France in 1880, incubators for premature and weak infants had arrived in some North American hospitals and at fairs and exhibitions by 1900. Early models kept the babies isolated from the environment, regulating the temperature and often the kind of air that the baby was breathing. Proponents argued that this allowed a baby born too early to continue developing as they would have in utero. The first strand of my research will compare what was known about uterine physiology and fetal development with particular elements of incubator design. I ask whether and how this technology embodied and responded to that knowledge.

This is a story about knowledge, or ignorance, of women's bodies, and it is also a story about race, ability, and disability. Incubators arrived as eugenics was flourishing in the United States and Canada, and in some ways, these were anti-eugenic devices, allowing so-called "weak" infants to survive. But as uniform, mechanical replacements for mothers' bodies, these machines also symbolized a eugenic ideal of a perfect body, stripped of all difference. Within a history of larger reproductive injustice, I expect to uncover uneven access to this technology and different levels of consent to its use across social groups.

I have won a short-term fellowship to conduct research for this project at the Huntington Library, and a Lemelson grant to support a research trip to the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. in 2021.

In this new project, I investigate the design of early infant incubators, devices which seemed able to replace or even improve upon mothers' bodies and care in particular ways. Invented in France in 1880, incubators for premature and weak infants had arrived in some North American hospitals and at fairs and exhibitions by 1900. Early models kept the babies isolated from the environment, regulating the temperature and often the kind of air that the baby was breathing. Proponents argued that this allowed a baby born too early to continue developing as they would have in utero. The first strand of my research will compare what was known about uterine physiology and fetal development with particular elements of incubator design. I ask whether and how this technology embodied and responded to that knowledge.

This is a story about knowledge, or ignorance, of women's bodies, and it is also a story about race, ability, and disability. Incubators arrived as eugenics was flourishing in the United States and Canada, and in some ways, these were anti-eugenic devices, allowing so-called "weak" infants to survive. But as uniform, mechanical replacements for mothers' bodies, these machines also symbolized a eugenic ideal of a perfect body, stripped of all difference. Within a history of larger reproductive injustice, I expect to uncover uneven access to this technology and different levels of consent to its use across social groups.

I have won a short-term fellowship to conduct research for this project at the Huntington Library, and a Lemelson grant to support a research trip to the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. in 2021.

Current Controversies in Plant Biology

(with Delia Gavrus, University of Winnipeg)

Over the last decade, a small group of ecologists and plant physiologists have started to argue that plants exhibit consciousness. These claims have captured the imagination of wider audiences even as they have been met with fierce criticism from scientists in multiple fields. As we examine the social dynamics of this controversy, we hope to uncover the different epistemic, ontological and ethical commitments at the heart of the debate. Some of these arguments appear quite familiar to historians of science, echoing elements of Romanticism in the early 19th C and eco-feminism in the 1970s. A main goal for this project is to situate this current controversy in this longer history.

In the first phase, we are conducting interviews with scientists involved in the debate, asking what they see as the main points of disagreement and how they have used media to engage public audiences. In these conversations, we are discovering very different articulations of the goals and methods of science, as well as the perceived relationship between modern science and Indigenous knowledge traditions.

(with Delia Gavrus, University of Winnipeg)

Over the last decade, a small group of ecologists and plant physiologists have started to argue that plants exhibit consciousness. These claims have captured the imagination of wider audiences even as they have been met with fierce criticism from scientists in multiple fields. As we examine the social dynamics of this controversy, we hope to uncover the different epistemic, ontological and ethical commitments at the heart of the debate. Some of these arguments appear quite familiar to historians of science, echoing elements of Romanticism in the early 19th C and eco-feminism in the 1970s. A main goal for this project is to situate this current controversy in this longer history.

In the first phase, we are conducting interviews with scientists involved in the debate, asking what they see as the main points of disagreement and how they have used media to engage public audiences. In these conversations, we are discovering very different articulations of the goals and methods of science, as well as the perceived relationship between modern science and Indigenous knowledge traditions.